Manufacturing Focus—A Comprehensive View

Infrastructure & Organization

Infrastructure Focus

Equipment, systems or people may support production without processing the product directly. Such elements are part of the infrastructure. Infrastructure may be physical (facilities) or non-physical (people--information—organization). While somewhat unusual, infrastructure can also be a focus criteria.

Specialized and expensive facility requirements may necessitate facility focus. Aircraft manufacturers (for example) bring together operations requiring high bay facilities. Such disparate operations as assembly, welding, machining and test may require such high headroom facility for specific parts or products. Such a requirement may bring together dissimilar processes, products and activities which share only a common need for headroom.

Non-physical infrastructure is occasionally a basis for focus. A world-wide manufacturer of toiletries concentrated perfume blending at a single site. The specialists there possessed olfactory skills essential to both new product development and production quality control.

As mentioned before, an argument can be made that only market focus is acceptable since customer satisfaction is the primary goal. However, a pure market focus may not account for the real limitations of manufacturing processes and infrastructure. Moreover, it provides little basis for the planning and layout of a production facility.

Matching the Layout and Organization

Organizations have a focus or lack of focus just as plants and departments do. When the reporting structure groups people with similar job functions, the organization has a functional focus. Product-focused organizations group people according to the products they manage. The criteria commonly used to focus sites and cells also apply to organizations.

Unfocused and inappropriately focused plants, layouts and organizations have handicapped many Western manufacturers. An even more serious situation exists when the focus of the layout differs from the organizational focus. This can happen when, for example, manufacturing departments focus on product lines while the supporting organization has a functional focus.

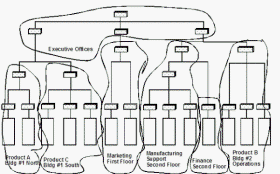

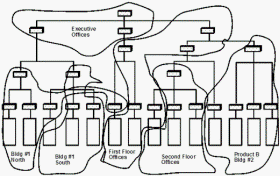

For facilities planning work, a useful tool has been developed to test the consistency between organization and layout focus. The analyst first prepares a detailed and up-to-date organization chart. Every person at the site is represented. The analyst then draws an envelope around those persons whose normal workstation is within a given contiguous area.

The envelopes may be compact and include only people on the same branch of the organization tree. The layout and organization are then consistent. Fig. 15.6 illustrates this. Official channels of communication coincide with the layout and those who communicate have workstations in close proximity.

In other instances, the envelopes may appear disjointed, stretched and generally 'messy' as in Fig. 15.7. This indicates a mismatch between layout and organization. People have workstations far removed from their superiors, subordinates and colleagues. Such a situation makes for poor communication along the chains of command.

Focus for time-Based Competition

Stalk (1990) and Blackburn (1990) suggest that time-based manufacturers, most of whom are Japanese, are moving away from focused factories. Such companies emphasize flexibility in their production facilities and produce a wide range of products at comparatively low volume.

From a traditional perspective, flexibility and low volume lead towards process focused functional layouts. Functional layouts are, after all, a very flexible manufacturing approach. But process focused factories seldom provide fast or even reliable throughput. They do not meet the requirement for fast response that time-based marketing requires. If the concept of focus is no longer valid in a time-based world, it raises again Roger Schmenner's question, 'How should you organize production?' (Hayes and Schmenner, 1978).

In an attempt to re-answer Haye's and Schmenner's question, additional issues came to light:

- What is a product?

- What is flexibility?

- How can we gain flexibility?

What is a product? The answer may seem self-evident. Experience in planning production facilities, however, shows that answers often are controversial, vague and contradictory. A workable answer depends on the purpose of the question and the perspective of the respondent.

Marketing people usually view a product mix by market segment or the product function. A manufacturer of aircraft engine parts views them as GE, Rolls Royce or Pratt and Whitney products. A manufacturer of commercial light fixtures sees its products as either 'specification grade' or 'architectural'. A market-oriented definition may be appropriate for manufacturing strategy and factory planning, but only when each product requires unique processes, unique procedures or has unique performance criteria.

A product engineer would normally define products by part number or drawing number. They would most often group similar products by function or appearance. Product engineers thus think in terms of bearings and bushings or turbine blades and compressor blades.

For manufacturing strategy and factory design, a product definition is suggested based primarily on process similarity. If items can be manufactured in the same sequence on the same equipment, they are in a single product group. If, in addition, these items require no significant changeover, they are for manufacturing purposes, considered as identical products.

Note that the above definition states that products are in the same family or group if they can be manufactured with the same process. This implies process standardization. It also implies that a revision of process technology may or equipment may change the product definition.

Hill (1985) suggests that only market requirements are a proper basis for focus. But situations requiring identical products to be made in different factories or departments due to different market requirements are unusual. In practice, it has been found that defining products on the basis of their process similarity generally brings one of the following results:

- The process-oriented definition corresponds to market-oriented definitions.

- Different markets make similar demands on manufacturing.

- The differing market demands are not contradictory.

Here are some examples:

Conplastics Corporation extrudes vinyl products, such as vinyl pipe, conduit and guttering, for the building industry. The marketing people classify their markets as 'wholesale' and 'retail'. Wholesale customers operate large chains of home-improvement stores or lumberyards. Retail customers are small lumberyards or home-improvement contractors.

These two markets make quite different demands on the sales department, requiring different personalities, discounts and order procedures. But to manufacturing, these market differences are transparent. The large wholesalers actually order and ship for individual stores, with such orders being similar in size and mix to those for retail stores. Retail contractors usually accumulate several contracts before ordering, and several contractors may combine orders for each shipment. These shipments are similar as well.

For manufacturing, the important product differences are those features which require major changeovers or different sizes of extruder, not who the end customer is.

Flexibility

By flexibility, most manufacturing people mean the ability of a factory easily to adapt to varying conditions. Both economy and speed are usually implied. While cost and response time go together, they are in fact different issues. The conditions referred to may include changes in:

- Product mix

- Volume

- New products

While these three types of flexibility are sometimes related, they are also separate issues which should be addressed individually in different ways

An extrusion plant can easily vary its output but rapid changes in product mix may require expensive setups.

Flexibility and improved response time will be important future issues for many manufacturers. How to achieve them needs to be examined and trade-offs are also involved.

Process focused factories and departments are the long-accepted means to attain flexibility in product mix, volume and often in the introduction of new products. However, they do not perform well on delivery speed or reliability. Process focus is an inadequate strategy for the time-based competitor.

Group technology cells achieve good flexibility within the range of their product families. In addition, new products often fit well in existing families, which eases their introduction. GT cells also have good response, with low inventory and fast throughput.

Another approach to flexibility is process technology (as distinct from process focus). Certain technologies may lend themselves to faster changeovers. This provides high product mix flexibility. Some technologies have lower tooling costs than others, which increase new product flexibility. Numerical control machine tools, for example, are highly flexible for both product mix and new products.

Flexible processes are not necessarily sophisticated or expensive. Manual methods are often quite flexible and should not be discounted. Small sacrifices to direct labour productivity can bring large benefits in productivity of capital, material flow and support requirements.

Toyota approaches product mix flexibility by dedicating simple, inexpensive machine tools to particular products, which seems an anomaly. They then merely turn the machine off if that product is not required. They thus achieve good mix flexibility with only a small trade-off in floor space.

The use of dedicated but small-scale equipment can also bring new product flexibility. A manufacturer of sheet metal products is an example. This firm specializes in sheet metal parts for defence electronic systems. They have many new contracts with low production for a number of years. When terminated, most products do not return. This firm has achieved flexibility by using simple conventional sheet metal forming equipment arranged in manufacturing cells. Their equipment, however, is not bolted to the floor. Each piece sits on a skid and is connected with flexible rubber cord to a receptacle. It can be moved with a fork truck in only a few minutes. With this concept, one-product workcells are rapidly put together and then disassembled when no longer required.

Manufacturing Focus and Plant Design

Relationships exist between product definition process selection, and production mode. For success, these must work together in a coherent manufacturing strategy. For success in a time-based market, they must satisfy requirements for quick response and rapid new product introduction.

The time-based competitor will most likely choose a manufacturing strategy which emphasizes workcells. Group technology cells will combine with flexible process technologies. A time-based competitor might also use simple conventional tooling in a dedicated workcell.

Time-based competition does not negate the advantages of product focus. It simply requires it at a lower level and smaller scale. Defining the product mix in terms of process commonalities clarifies the idea of manufacturing focus and permits a more universal application.

Manufacturing Focus and Manufacturing Strategy

The focus criteria selected should be consistent with corporate goals, market strategy, manufacturing processes and infrastructure. Developing such focus is one of the most important elements of manufacturing strategy. Focus is our best means to reduce manufacturing complexity and direct technical and knowledge resources at customer demands. By doing this, it makes manufacturing an integral part of the corporate strategy rather than merely being a hapless supplier of commodities.

References

Blackburn, Joseph D. (1990) Time-Based Competition, Business One Irwin, Homewood, Illinois.

Hayes, Robert H. and Wheelright, Steven C. (1984) Restoring Our Competitive Edge, Wiley, New York.

Hill, T. (1985) Manufacturing Strategy, Macmillan, London.

Voss, Christopher A., Manufacturing Strategy--Process & Content, Chapman & Hall, London, 1992.

■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■